On the second day of the new year, the front page of the Courier Journal highlighted the fact that one of our local hospitals was third in the United States in the number of spinal fusions performed. Since the Louisville business community has identified generating healthcare revenues as a top long-term strategic priority, the headline could easily be interpreted as a success story. However, the full-page article by John Carreyrou and Yom McGinty reprinted from the Wall Street Journal was not very flattering. (The article is not present on the Courier Journal website, but is available on the Wall Street Journal’s.)

The article emphasized the multibillion-dollar annual market and the medical controversy over when and if this extremely expensive major surgery should be done. Also highlighted were the large amounts of royalty money paid by the manufacturers of surgical equipment directly to surgeons who make the decision to operate. The article reported that five of the surgeons at my local hospital received more than seven million dollars in less than a year from the manufacturer of the implants used in the surgery. This was in addition to the clinical charges billed. It was reported that total Medicare reimbursements for spinal fusion at my local hospital were almost $48 million. The article proposes, and I and would have to agree, that the amounts of money involved are enough to distort the medical decision-making process. Since the hospital and doctors involved are part of our academic medical center, one might also reasonably assume that young physicians in training will perceive these activities as the standard of care.

There is not room here today to summarize the medical literature pertaining to spine surgery for disc disease and arthritis. Suffice it to say, most national organizations of general physicians and rheumatologists are arguing for fewer operations than in the past. In my own career as a rheumatologist, I personally recommended spine surgery for only three patients with arthritis. It is possible for you to suspect that I think too much spine surgery is being done in general. The hospital and doctors involved will likely offer their own explanations: indeed I think they will need to.

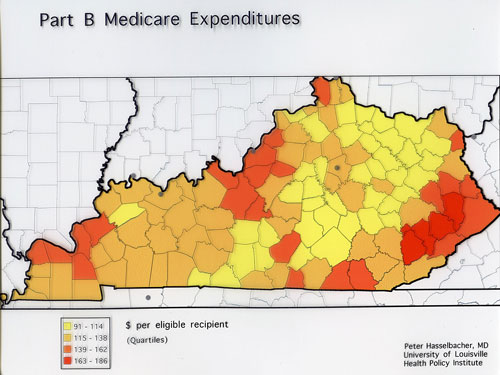

What I do want to talk about today, is the methodology that brings such observations to the forefront. It has been called study of “small area variations.” You see these kind of studies all the time. They were popularized by Dr. Jack Wennberg and the group at Dartmouth. I have always been drawn to this approach because the mapping of results appeals to my visual sense. For example, here is one of the earliest health policy studies I ever did.

I made a map of Kentucky and shaded each county with the average yearly amount of money in the early 1990s that Medicare paid per eligible non-disabled recipient. I was stunned. There were clusters of counties in eastern Kentucky where the expense for the average Medicare patient was double that in the least expensive areas of the state. There were substantial differences between the areas around our state’s two medical schools in Louisville and Lexington.

These kind of studies can be called “observational” studies. They do not have the scientific power of controlled experiments. Sometimes the method is disparaged because it generally does not provide proof for causation. This doesn’t bother me because much (if not most) of science begins with observation. I like to call area variation research, “experiments of nature.” It can make use of preexisting data and is comparatively inexpensive to conduct. Why waste information? The results may not allow a clear explanation for differences, but the dramatic and routinely observed differences in things like medical utilization and expense just beg to be understood. Potential explanations deserving of further inquiry can usually be generated.

This kind of analysis can be particularly useful in health policy research because it does not reflect any particular preexisting bias or imply right or wrong. “I am here– explain me!” the data says.” Did Peter Hasselbacher recommend too few patients for spine surgery? Were the Medicare patients in eastern Kentucky sicker? Did they and those in other high cost counties have better access to doctors? Do other social factors affect medial expense? Were all the other counties underserved? Is it a matter of local practice habits or quality of care? Is it access to specialists? Is it highly efficient billing practices? Is it fraud? Given the staggering burden of both illness and medical expenses that drag down families and our economy, wouldn’t you like to know?

I am very much in favor of making more information available to the public as a whole. Why can’t I have the same access as the reporters of the Wall Street Journal? (Perhaps I do and don’t know it!) If I have to go to a hospital again, I would like to know which are having trouble with hospital-acquired infections, or how many of a given service they do. Right now, most of what I have to go on is mere promotional puffery. Yes, data will be misinterpreted and even misused. Isn’t it always? However, there are plenty of people and organizations that are willing to help with the interpretation, and we as a public can learn to become better users of the information. In our current market, hospitals, doctors, and other healthcare providers are free to announce that they are “The Best.” It is only fair and proper that the rest of us be able to independently verify their claims.

Feel free to comment.

Peter Hasselbacher, MD

10 Jan 2011