How can we tell where it is headed?

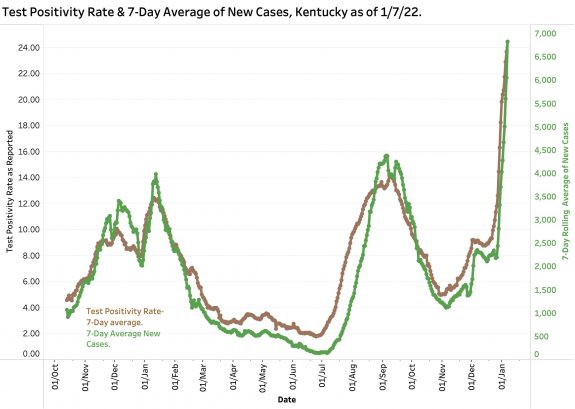

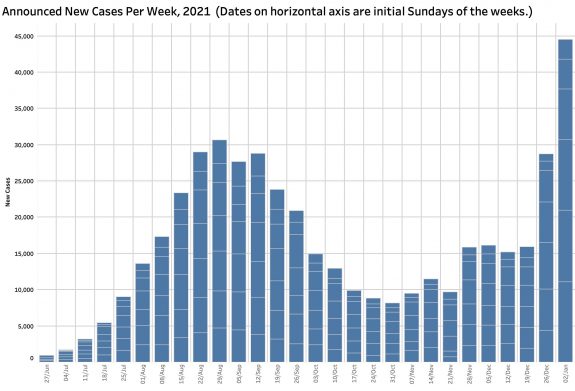

Today is Sunday January 9. The last iteration of Kentucky’s Covid-19 epidemic data was issued to the public, (and presumably the CDC) last Friday. The next set of data will not be available to the public until tomorrow evening. That leaves a gap of three full day’s history of epidemic expansion that is already the fastest of the previous 670 days. [Although we can expect that the weekend reporting days of Sunday and Monday may be low, those days can be compared to pervious weekend days.] Daily detected new cases and the proportion of viral tests that are positive have never been higher in Kentucky by wide margins and are rising with exponential fury in a straight line since December 27. One of two major factors behind the present COVID explosion is the new Omicron variant that has been sweeping through the rest of the world and likely been in Kentucky since December. Omicron is by far the most is the most transmissible COVID variant yet to hit America. It is likened in virulence to measles which up to now has been considered one of our most infectious diseases. The second expansion driver was a holiday season in which we believed and may have been told it was safer to travel and visit with others– and we did! However, I believe we carried that permissiveness too far. For example, today’s Courier-Journal contained some holiday photos including a fun-looking party with dancing and consuming in which no mask was in sight, and UofL basketball game with all naked faces in the audience. The stage was set, and the virus was willing and more than able (as if we could ascribe to a virus with purpose).

A lot of major outcomes are still up in the air. We know that wildfire is not an exaggeration when we consider a virus that can double its hosts in a matter of days. There is evidence that Omicron does not cause as severe a disease as Delta or other previous strains. There may be more upper respiratory involvement and less pneumonia or systemic manifestations. People may not need to go to the hospital as frequently, and when they do may not need ventilators or die as often. There is so much COVID in the community that even people in hospital for hernia repair may test asymptotically positive. There is a wishful hope that the rapidly rising case counts will fall as quickly as they rose in an “ice pick” configuration rather than a broad months-long peak as previous surges did There is a speculative possibility that survivors of Omicron will be more resistant to reinfection of either the vaccine breakthrough or natural variety. Unfortunately, we already know that some of the effective treatments of Covid-19 are no longer effective or less so.

We already know that at least some the current antigen or take-home tests for the virus are not as sensitive. We know that infected persons may be symptomatic less often but not how much so. Neither are we sure yet how soon or how long infected persons, symptomatic or not, are able to pass their disease on to others. We already know that it easily infects previously vaccinated individuals or those who have recovered from “natural” infections. Omicron has not been around long enough to tell if there will be significant long-term complications. In effect, it is as if we are dealing with a new disease. Answers to these uncertainties will eventually emerge from coordinated public health investigations in homes, offices and hospital, and in the laboratory. Sadly, our neglected and fragmented public health and general healthcare systems have already shown their weaknesses. We will also learn from other countries with more integrated and universal healthcare systems that can collect information from large numbers of diverse individuals relatively quickly.

What will I try to do in the meantime?

Since the beginning of Kentucky’s version of the COVID epidemic, I have been collating the relatively limited data available presented at first every day, and more recently only recently 5 days a week to attempt to answer the question: How can we tell if we are winning? Readers of the previous 68 articles on these pages dealing with the epidemic will be aware of the data manipulations and visualizations I use to address this basic question. Categories of data used include cases, deaths, tests, hospitalizations, ICU and ventilation utilization, and two ways to calculate test positivity rates. For the past nearly two years these metrics have tracked each other in predictable ways. My previous estimations of trends have been mostly on the mark. When Monday’s numbers are made public, I will apply the same approaches I have been using to ask if we are winning yet. Right now, we are losing– and badly!

You can interact with up-to-date data yourself on KHPI’s Tableau Public website. I posted a few Tweets since my last article @HealthPolicyKY.

Peter Hasselbacher, MD

Emeritus Professor of Medicine, UofL

President, Kentucky Health Policy Institute

Sunday, 9 January 2022

Here are a few figures from the data of January 7.

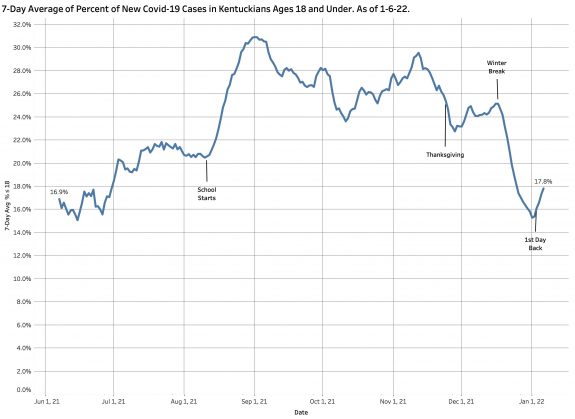

I will have more to say about COVID in people 18 and under later. It is clear that individuals in this school-age group contribute significantly to the totals. In early September these individuals made up as much as 32% of that day’s total discovered cases. Note large swings when school starts in August and at the beginning of winter break.