Perhaps the most innovative aspect of the 1983 contract under which Humana assumed management of our state-owned University of Louisville teaching hospital was the Quality and Charity Care Trust Agreement (QCCT). In exchange for a fixed minimum of financial support from the City of Louisville and the State of Kentucky to fund indigent inpatient medical care, Humana promised to provide all necessary indigent care to eligible citizens of Jefferson County and to a limited number of out-of-county individuals. It appeared to me at the time that the arrangement worked well, but I came to realize that as a consequence, the brand-new University Hospital would be explicitly defined for the community as a trauma center and poor-people’s hospital. To the extent that University Hospital inherited the mantle of the formerly segregated Louisville General, University Hospital remained the place where people of color, those at the margins of society, or those served in the teaching clinics of the medical school were expected to be cared for. Private patients were admitted elsewhere. The Hospital has yet to shed this unfortunate constraining heritage. I have written a fair amount about this program.

The initial amounts of money promised were relatively modest: $2.1 million from the city and $14.8 million from the state with a formula for annual increases. In 2012, the State was contributing $29.6 million and the City its highest ever $9.6 million. In reality, the potential cash flow for the hospital could be much greater. Because University Hospital was considered to be a government entity, by means of a complicated Inter-Governmental Transfer mechanism (IGT), the state was able to match the combined new funding with additional federal Medicaid money at a handsome multiplier. The lower the average income in a given state, the greater the bonus. Currently Kentucky has the 6th highest multiplier at 2.39. (See table and map.) Thus, for every $100 added to its Medicaid expenditure, the state picks up additional $239! Communities like this infusion of cash into their local economies. Would that such IGT funding was always used for medical purposes but it is no secret that the matched money was often returned to a state or local entity and used for other purposes. The Feds picked up on what it began to call the Intergovernmental transfer scam and took steps to reign it in and demand accountability. I recall that University Hospital set aside some $50 million in the event of a claw-back. Entities using the IGT methodology have to be more careful, but the practice did not cease and provides an explanation of the bickering between the University and the City or State over failure to return its “rebate” to use for unstated University purposes. More about this below.

When it became apparent the Hospital was receiving more indigent care funding than it needed, when it became known that the University was capturing Hospital profits for other uses, when issues of transparency and accountability arose, when the Kentucky State Auditor rendered an unflattering report, and when state and city budgets became tighter, both governments began to back down their contributions. Although the QCCT contracts began to unravel on their own for these and other reasons, the event that changed the landscape and led to a complete withdraw of City and State contributions was the passage of the Affordable Care Act – also known as Obamacared. In the blink of an eye, the number of uninsured patients fell away and University Hospital became quite profitable without any QCCT funding. It still is! In 2015 its earnings before interest, depreciation and amortization (EBIDA) was 16.3% at a time when sister Jewish Hospital was losing money. It is a common belief among the faculty that the recent change in University Hospital management resulted from the refusal of its former President to make a multimillion dollar transfer. In previous years, money was transferred from Hospital revenue to the University proper for research and other non-clinical uses. I do not know if that practice continues. It is enough to say that in the era of Obamacared, University Hospital is carrying more than its own weight.

Zeroed out.

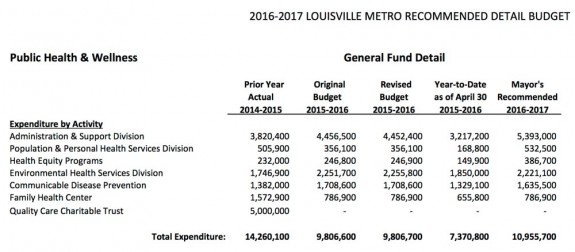

Recognizing that an additional taxpayer transfusion was no longer necessary, both the State and City rapidly withdrew their funding. Earlier this year, Governor Bevin vetoed a state contribution to the QCCT of up to $7.5 million that had been passed by the legislature. The City eliminated its contribution in its last budget year, and the new budget for 2016-17 recommended by Louisville’s Mayor Fischer zeroed out the city contribution once more.

It was already dying.

The QCCT was always an evolving entity. I reviewed all the QCCT contracts (see links) from the beginning. Several changes had been mutually agreed to in the past to iron out a variety of wrinkles and to adapt to changes in the law or local circumstance. However, for all practical purposes, once financial support began to be withdrawn, the QCCT covenants ceased to exist. The hospital was no longer under any obligation to provide all necessary indigent care. In fact, although it has complained about the withdrawal of funds, current Hospital manager KentuckyOne Health is not even a signatory to the QCCT. To keep the IGT process within the governmental family, it is the University of Louisville and its women’s hospital-within-a-hospital, still managed by University Medical Center, Inc., that is the signatory to the current contract and designated to get the money. (Indigent care support for women only, or illustrative of the fig leaf nature of the women’s health carve-out?)

You might then reasonably believe that the QCCT has ceased to exist, but that is not the case. Zombie-like, the QCCT still remains as an associated corporation of the University of Louisville with a Board of Trustees made up of predictable suspects. According to the last report available to me, a $5 million contribution was made, not by either State or City, but by the University of Louisville itself. I must assume that a Medicaid match is still being made or else why would the University put up the money? Indeed, from what University account or affiliated entity is the money coming from? I have no idea how the $5 million or any Medicaid pull-down is ultimately being used but past precedent troubles me. It does not appear to be needed for inpatient indigent care at University Hospital. Perhaps someone will straighten me out.

Do we still need a QCCT fund or something like it?

There will probably always be a municipal need to provide medical care for those excluded from our current private and government healthcare systems. Such care can be subsidized only so far on the budgets of hospitals and healthcare professionals. People who show up in emergency rooms must be taken care of, but non-emergency care to keep people out of hospitals is equally important and essential. The same Obamacared program that made many safety-net hospitals profitable has been a lifesaver to safety-net outpatient primary care clinics. The availability of Medicaid and ACA money made it possible to accommodate patients from other than Jefferson County and to offer additional important services. However, this enviable situation for providers and patients alike may not last for long. The same Governor that vetoed a state contribution to the former QCCT has also vowed to roll back the very Medicaid expansion that lifted University Hospital to profitability. How will this not return us to the bad old days of an inner-city municipal hospital that the majority of the community is reluctant to go to? Governor Bevin offered the argument that he must roll back the fruits of the Affordable Care Act because augmentation of Medicaid is “unsustainable.” He may well be right, but it is no more or less sustainable than all the rest of our healthcare non-system including Medicare and employment-based health insurance. Medicaid must and will evolve – as the system as a whole must – but the straw-man of unsustainability cannot be used to justify throwing the most vulnerable of us under the bus.

We may need something new after all – but different.

I have long argued that the QCCT program as it was begun had outlived its time. Yes it provided hospital care for the needy, but at a price. It doomed the Hospital to perceived if not actual second class status and maintained a two-tier system of care within the University Medical Center defined by income and race. The uses of the money were not fully transparent. The program did not provide for the medical care of children in poverty. It did not provide for indigent care in other hospitals. It did not cover essential outpatient care. It did not cover outpatient drugs. It caused tension when individuals in adjacent counties asked for help.

Should we need a continuing, discrete, indigent care fund; I do not support a return to the QCCT. Put a stake in its heart. Money should follow the patient, not the institution. No individual should be considered part of a captive group of patients– not the poor, not the mentally ill, not our veterans, nor people of color. All facilities in Louisville should serve their fair share of indigent or underinsured citizens. Are not all general hospitals in Louisville nonprofit institutions excused from paying taxes in exchange for community services? In any future indigent care fund, more accountability and transparency is mandatory. The financial control of the funds should not be left in the hands of the University or any other entity that is a recipient of such public funding. Should our assistance still be limited to citizens of Jefferson County?

Such a program change will be good for medical education too. Without a diverse mix of patients and their different illnesses, medical education will always be substandard. A hospital full of poor people tends to treat its patients like poor people – not a good example for trainees. It would be wonderful to see a single standard of care within our University Medical Center where all patients enter through the same door and are cared for in the same beds and clinics. We currently have separate private offices and teaching clinics. In fact, the stated goal of the University of Louisville and KentuckyOne is to use Jewish Hospital as a “private” teaching hospital. I recognize that the dichotomy described above is not unique to our city or our Medical School, but is there no other way? Yes, providing even basic medical care is a daunting challenge, but one we must assume. This must not be thought of as an unselfish undertaking. We are as a society no healthier than the least among us.

Peter Hasselbacher, MD

President, KHPI

Emeritus Professor of Medicine, UofL

10 July 2016

I have been following this issue for some time and believe I have the facts right. If not, help me correct the record. How would you structure a system of medical care for those not part of employment-based health programs or traditional Medicare or Medicaid?

One thought on “Indigent Hospital Care in Louisville at a Crossroads.”

Comments are closed.