FDA and Medicare Records reveal Sackler-Associated Drug Companies as Leaders in Controlled Substance Markets.

In the Pre-Covid Era, almost every day’s newspaper would contain at least one article about our last-worst epidemic of opioid abuse. Since Covid-19 justifiably soaks up much of our attention, the infrequent article about opioids now takes me by surprise. The odd article that leaks through reminds us that the opioid tragedy has not gone away. Indeed, as the desperation attendant to Coronavirus spreads, there is every reason to believe that the fellow-traveler of opioid abuse is blossoming also. The current news environment has allowed the progress of previously reported high-profile litigation against an assortment of opioid manufactures, marketers, and sellers to proceed in the relative background.

Last week, the United States Department of Justice announced that one arm of litigation came to a head when Purdue Pharma LP pled guilty to three felony charges related to its marketing and distributing of OxyContin. The settlement agreement (subject to bankruptcy court approval) includes a payment of $8.34 Billion, but to whom or what is not clear to me. Since Purdue declared bankruptcy, it seems unlikely that anywhere near that amount will ever be paid. Companies don’t go to jail. Even billions of dollars can be an tolerable cost of doing business in Big Pharma. As part of a broader overall settlement, the Sackler family owners of Purdue resolved a number of additional civil charges for $225 Million. Some commenters have expressed opinions that the Sacklers and Purdue are getting off easy. That may well be so, but the Justice Department’s announcement notes that “the resolutions do not include the criminal release of any individuals, including members of the Sackler family, nor are any of the company’s executives or employees receiving civil releases.” In my opinion that is eminently proper.

How involved were the Sackler companies?

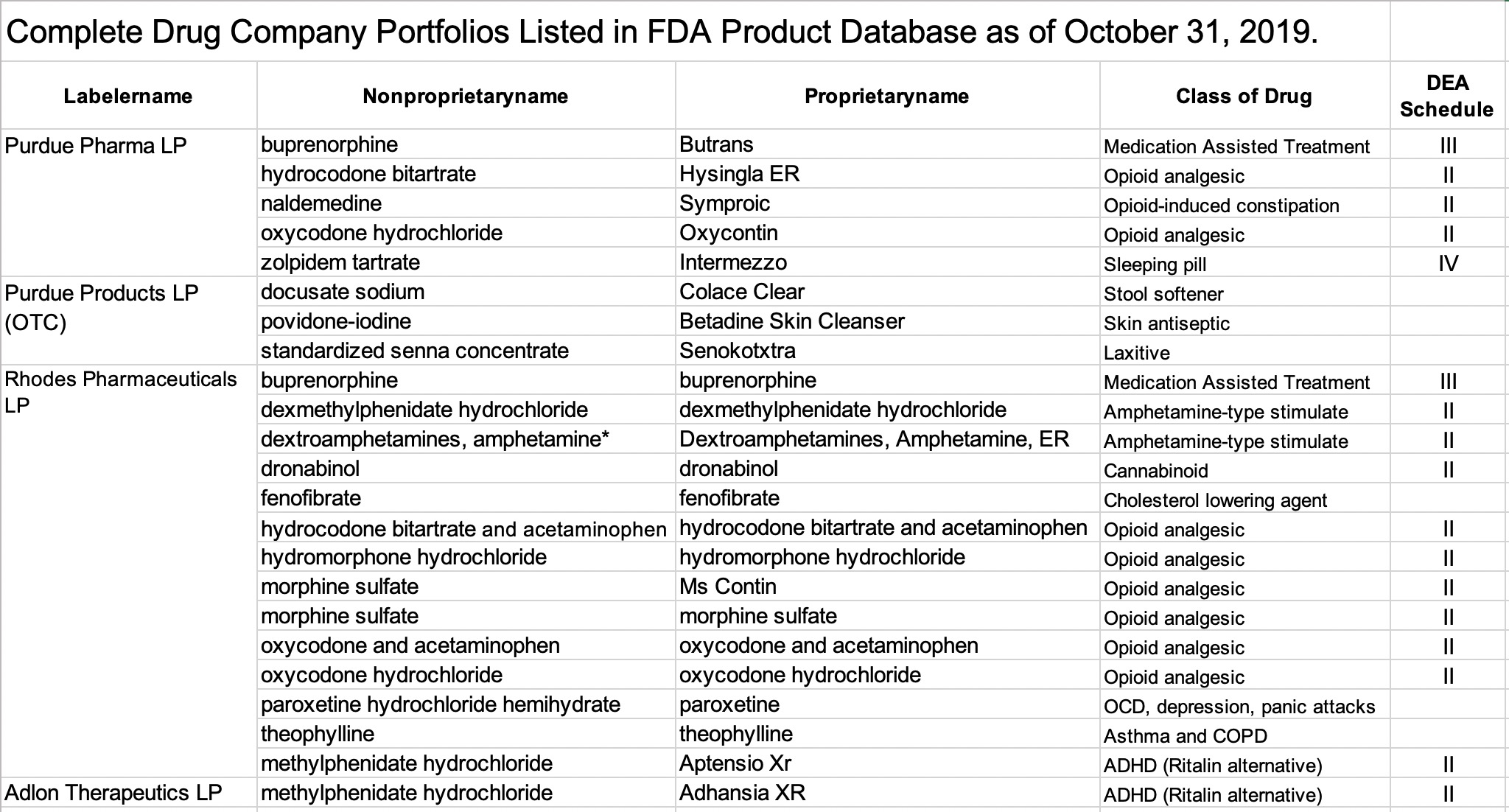

Back in late 2019 BC (Before Coronavirus), I began an article about the overall drug portfolios of the most prominent defendants in the opioid lawsuits that were brought by individuals or governments of which I was aware. That effort got put back on the back burner by the virus, but the current settlement offer and publication in March of a book that I will reference below stimulated me to go with what I have. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) maintains a public-use data file that catalogs drugs under its jurisdiction. The set of linked files is tricky to unpack and even harder to understand, but contains a wealth of information about generic, proprietary, and over-the-counter (OTC) drugs all of which are categorized by manufacturer, class of drug, and many other factors. I cannot claim that all drugs made or marketed at any time are present in this listing, but when I started to extract the portfolios of companies that were involved in opioid litigation, some results startled me.

I learned first from the Wall street Journal and later from other sources, that as litigation against Purdue Pharma advanced, the company formed the subsidiaries Rhodes Pharmaceuticals LC, and Adlon Therapeutics LP. I am unaware of the exact timing of the creation of these ventures, but both these companies appear in the FDA list in October 2019. In tables and discussion below, I will detail what I found in the FDA database, and in a 2017 Medicare Part-D Drug Utilization Report for all three of Sackler-associated pharmaceutical firms that market prescription drugs. The short answer to the question posed above is that the Sackler-associated companies are almost exclusively focused on the manufacture and marketing of opioids and other DEA controlled substances and are at or near the top of short lists of companies with respect to the number of such drugs produced and the volumes consumed by Part-D Medicare patients.

Things are not getting better. Whose side is the FDA on?

One other factor stimulated me to drag this old data out of the pile on my desk was a book published just last March as the Covid-19 epidemic began. Its title is Pharma: Greed, Lies, and the Poisoning of America. This remarkable piece of investigative journalism by Gerald Posner traces the history of the pharmaceutical industry and efforts to regulate it from the late 1800s through the present. We have all heard the stories about heroin in teething lotions for babies, but I was surprised to learn that even some of the big-name, mainstream drug companies that were still operating during my professional career got their starts peddling drugs like heroin, morphine, cocaine, amphetamine, and cannabis. Such drugs create their own demand. They sell themselves as their addictive chemical virus enters the mainstream of society. Companies magnified demand for their drugs by introducing new models of drug promotion to public and professionals alike– including payments to physicians and other entities. It seems to me that many if not most the criticisms leveled against Big Pharma today have been out there relatively unchecked. Big Pharma has been calling the shots for decades. According to Posner’s well researched reporting and other public disclosures, the early founders of Purdue played a major role in what has evolved into Big Pharma’s current strategies for selling prescription drugs. It is a business model based in large measure on lobbying and advertising that was designed to be more effective for increasing the prices of drugs and the bottom lines of drug companies than it was for improving the health of the public. Even the FDA does not come out of this book looking like the protector we expect and need it to be. The FDA has always been subject to the same regulatory and political capture that in my opinion is occurring as I write this. Large fines and penalties against pharmaceutical companies have been applied in the past. It is not clear to me they have made any difference for the better in terms of public protection. Nor in my fears will any new round of fines and settlements make a difference if the game continues to be played with the same rules and using the same umpires. Given that the FDA will have important immediate roles in the nation’s handling of our current Coronaviruses epidemic, our continuing past failures to rationalize the drug industry is going to haunt us immeasurably in the near future. An industry that was comfortable gouging us for insulin is not going to change its spots willingly just because of a little thing like a deadly epidemic.

Comments on FDA database structure and data extracted for this article.

The remainder of this article may get a little technical! As a life-long writer of scientific articles and worshiper of data, I initially organized this article accordingly into “Methods, Results, and Conclusions.” My editor suggested that I not initially overwhelm a reader with dry numbers, so I am putting this part last. I do suspect you will be as surprised as I was by how opioid-oriented some companies are. Purdue is not alone in this focus. An Excel file with the FDA data being referred to is available in a new window or tab here.

Generic vs. Brand name.

As I understand it, “Labelername” is the technical term the FDA uses to identify companies under its jurisdiction that manufacture, market, distribute, or sell drugs. be they over-the-counter (OTC) or prescription drugs. Each drug in the list is identified with two names, a nonproprietary (generic or chemical name) and a proprietary (or brand name). When the two names are the same, the drug is being offered as a generic drug. When the proprietary name is different from the “generic” drug name, the drug is being marketed as a brand name. For example, Rhodes offers morphine sulfate as both a generic and branded version and thus it appears in the list for that company twice.

Mechanism of Action & DEA Scheduled Drugs.

The listings also include a brief summary of the class of each active drug in a given product, be it offered alone or in combination with other drugs. (Think of oxycodone by itself, or the combination of oxycodone & acetaminophen as in Percocet.) Some classes of drugs with potential for abuse are further categorized as “DEA Scheduled” drugs and are subject to stricter levels of regulation in manufacture and individual prescribing. For example, Schedule I drugs such as LSD or heroin have no currently accepted medical uses and a high potential for abuse. Schedule II drugs are “defined as drugs with a high potential for abuse, with use potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependence. These drugs are also considered dangerous.” Schedule II drugs include the “hard” opioids such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, and fentanyl; and amphetamine-like stimulants such as Ritalin.

Summary of Results by Company.

• The Sackler-associated firms are heavily, indeed nearly entirely involved in the marketing of opioids and other controlled substances as both generic and brand name products. This has been true for a long time. Of the twenty different line-item prescription drug entries in the FDA table for a Sackler-associated labeler, 17 are DEA scheduled (14 as Schedule II, 2 as Schedule III. and 1 as Schedule IV).

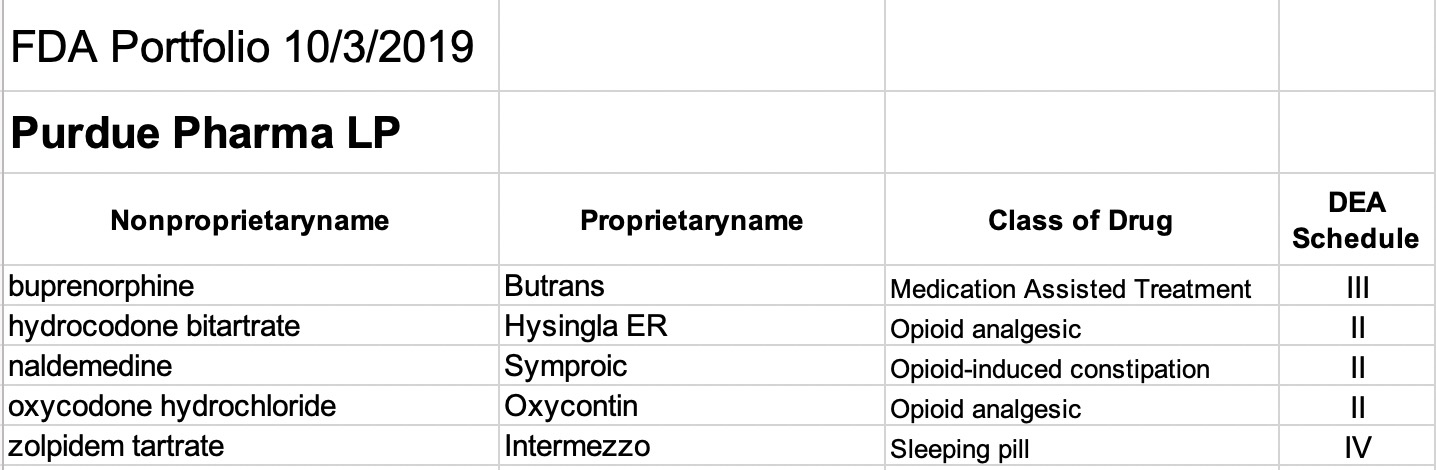

Purdue Pharma:

Excluding the three OTC drugs from Purdue Products LP (which I understand to have been products of the original ancestral Purdue company) all 5 of the drugs of Purdue Pharma LP are FDA scheduled substances. Two of these are extended release preparations of either oxycodone (Oxycontin) or hydrocodone (Hysingla ER). These are “hard” opioid molecules that have figured prominently in the opioid epidemic. Rounding out the offerings are buprenorphine, an opioid commonly used used in medication-assisted treatment programs for opioid addiction, and naldemedine which is a new opioid variation approved for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation in non-cancer patients. All of the Purdue Pharma (and Purdue Products LC) drugs appear to be marketed as brand names rather than as generic versions.

The only non-opioid marketed by Purdue Pharma is a branded version of zolpidem, a commonly prescribed sleeping pill. The FDA and Medicare have given strong warnings against using zolpidem in combination with opioids.

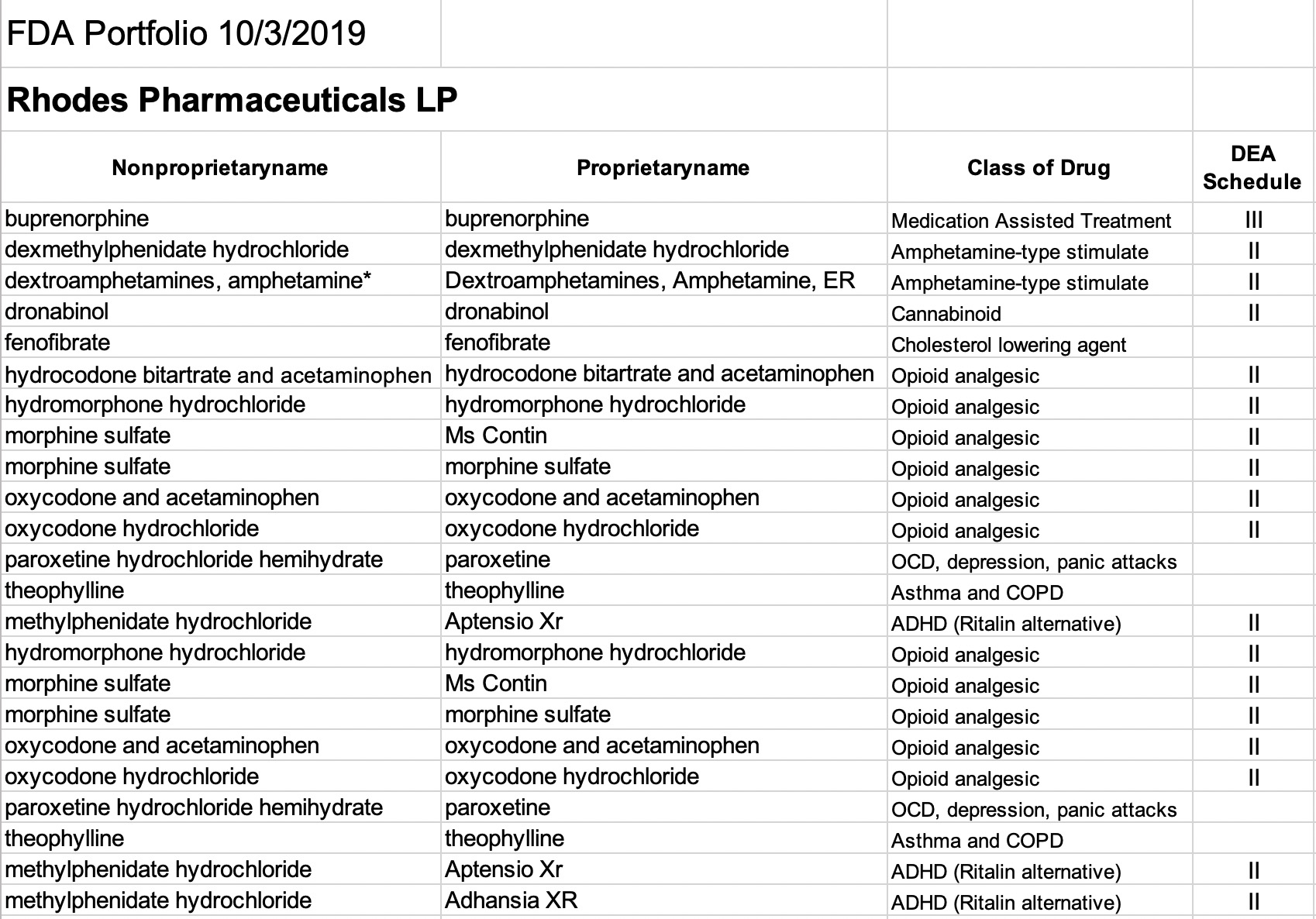

Rhodes Pharmaceuticals L.P.

Rhodes seems focused largely on generic versions of opioids and amphetamine-type stimulants. Of the 14 listed Rhodes drug entities, all but three are DEA-Scheduled. Two of the scheduled drugs are offered in both generic and branded versions– i.e. morphine sulfate as Ms Contin, and methylphenidate hydrochloride as Aptensio Xr.

Opioid analgesics offered by Rhodes include generic hydrocodone, oxycodone, hydromorphone, and morphine. Buprenorphine is entered as a generic only. Three of the entries are amphetamine-like drugs, two of which are long-acting varieties. Another controlled substance labeled includes dronabinol, a cannabis derivative used to treat nausea and vomiting due to chemotherapy. Paroxetine (not scheduled) is a psychoactive drug used to treat panic attacks, depression and obsessive disorder and is the ingredient in the brand name Paxil marketed by another company. The remaining two generic drugs, theophylline and fenofibrate, are non-scheduled drugs used to treat chronic pulmonary disease and to lower cholesterol.

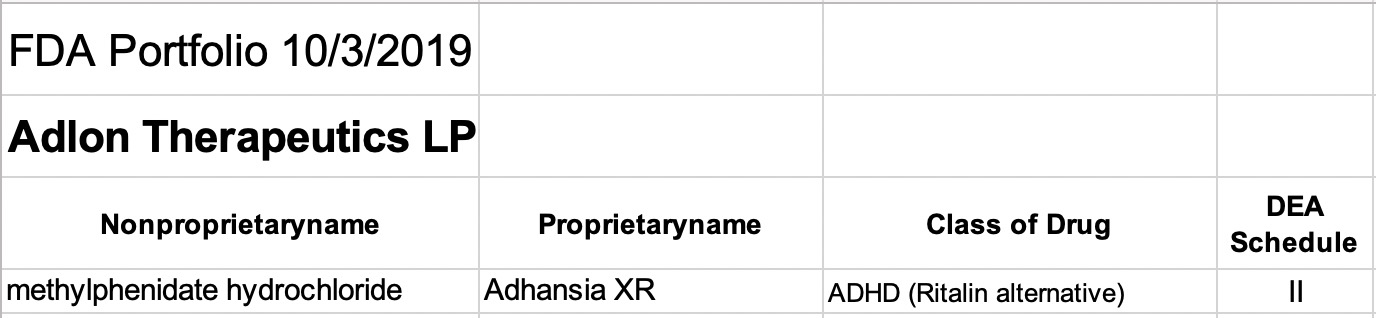

Adlon Therapeutics L.P.

This relatively new subsidiary of Purdue has a single drug listed in the 2019 FDA list examined here. The active molecule, methylphenidate HCl, is the same as that in brand name drug Aptensio Xr marketed by Rhodes. Both versions of the drug are listed only as brand name products by the two companies. This category of amphetamine-like drugs is approved for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) of children, but is also used and misused as diet pills, study aids, and for other FDA approved and non-approved conditions. Amphetamines have long been considered as drugs with large potential for misuse and addiction. That is why the FDA includes them with other Schedule II substances such as opioids.

More Details and Rankings.

These drugs are big business.

The FDA catalog above lists 7218 unique “Labeler” names which I understand to be the business names of firms that manufacture, market, or distribute FDA-listed drugs. Of these, some are obviously variations of the same company name differing only in details of spelling, punctuation, or capitalization. (For example, the chain store “7-Eleven” is spelled seven different ways!) For one of Rhodes drugs (Morphine Sulfate), “Rhodes Pharmaceuticals L.P.” appears as “Rhodes Pharmaceuticals L. P.” with a space between the ‘L’ and the ‘P’. I merged these two spellings together but did not attempt to correct the entire database! Of the 7218 unique company spellings, 231 had the string ‘opioid’ included in the ‘Pharmaceutical Class’ column of the database.

Multiple variations of the same non-proprietary drug.

Note that a single unique Nonproprietary drug name for any given company may often have more than one line-item record in the database. A single drug may appear several times for a single company because of differences in type of pill, strength, route of administration, packaging, or the like. Each of these product variations will have its own unique National Drug Code (NDC) and record in the database table. I analyzed the October 2019 FDA list above with this in mind. Of the 231 company names with at least one record containing ‘opioid’ in a Pharmaceutical Class description, 57 had at least than 10 records. Companies with more opioid-containing drugs and correspondingly more individual records appear to be distributers or repackagers of multiple drugs supplying entities such as hospitals or nursing homes. Even so, Rhodes Pharmaceuticals ranked #9 for overall number of records (37) distributed among 10 different ‘opioid’ drugs. Purdue Pharma ranked #25 for records (20) distributed among 4 separate ‘opioid’ drugs. Because of issues related to the history and construction of the database, these numbers should be considered as “back-of-the-envelope” estimates.

Medicare scores again!

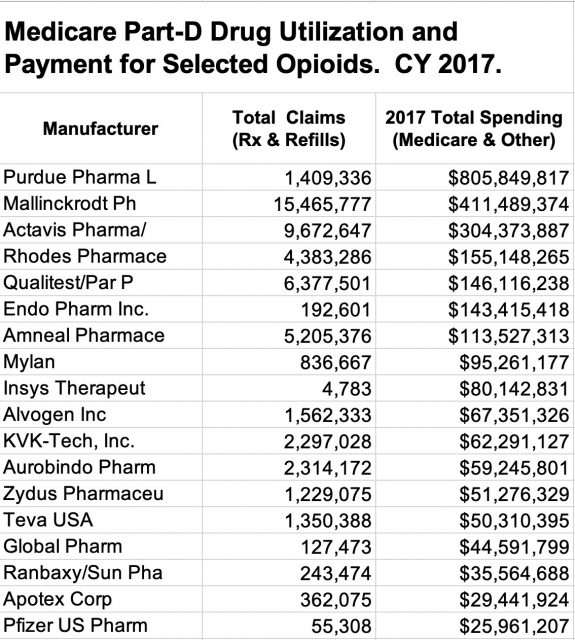

Additional relevant data is available in the Medicare Public Use Files for Part-D Drug utilization. These files include all ambulatory drugs covered by stand-alone Part-D Medicare drug plans or included in Part-C Medicare managed care plans. I have found these data to be usefully reliable! Using KHPI’s working definition of “hard opioids,” I extracted drug utilization data for calendar year 2017 from the PUF, Medicare Part-D Drug Spending YTD [2013]-2017. [This version of Medicare’s Part-D utilization studies is uniquely significant because it was compiled to compare the change in drug pricing over 5 years and included the name of the Vendors. I used these files in the past to study the rising prices of insulin and other drugs.] The data are available in an Excel file here. Below is a list ot the top 20 companies ranked by Total Amount Paid by Medicare, other payers, and the pocket of the consumer.

Purdue Pharma ranked #1 for Total Medicare Paraments for these opioids with $805.8 M. Rhodes ranked #4 with $411.5 M. Of interest, #2 was Mallinckrodt with $411.5 and #5 was Insys Therapeutics with $80.1 M. These latter two companies have been major defendants in recent ongoing civil or criminal opioid litigation. In terms of the raw numbers of prescriptions and refills written for these Medicare patients, the ranking was Mallinckrodt #1, Rhodes #5, Purdue #9, and Insys #53. These latter two rank relatively higher for cost than for number of prescriptions because their brand name products were on average more expensive. Insys is listed with a single product, Subsys, which is a version of fentanyl. Their product is one of the very most expensive Medicare drugs per prescription of any drug, and one of those with many legal problems.

Comment.

I have tried my best to understand the details of the FDA drug list so as to extract meaningful and accurate information. It should be no surprise to anyone who has grappled with issues of drug approval and prices that things are quite complicated. If I have made an error of fact or misinterpretation, I would appreciate knowing so.

Peter Hasselbacher, MD

Emeritus Professor of Medicine, UofL

2 November 2020