Earlier this month I published a survey of the cost of insulin to the Medicaid and Medicare programs of Kentucky and the nation. Fully 9.1% of the total cost of Kentucky’s outpatient Medicaid drug program went to pay for the several brands of Insulin still available. It was obvious that some brands cost a lot more per prescription or claim than others and that the most expensive brands were prescribed most often! I used this critically important drug as an example of how the market for prescription drugs in America is badly broken. Since then I stumbled on two additional federal databases that provide additional insight into how much these drugs cost at the local pharmacy counter where the rubber hits the road. These are federal surveys that determine the National Average Retail Prices paid by the consumer (NARP), and the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC) for the pharmacy. Both these programs provide data at the cost per milliliter level, and otherwise facilitate apple-to-apple comparisons of the different brands. In brief, the additional data confirm that in 2013, for the same size bottle, the newer insulin analogs cost 71% more than the older “human” insulins. By 2015, all prices had increased; some substantially. Valuable information about the retail prices of drugs is being kept from public inspection.

At the time I wrote the article, I was still blundering about in the deliberate darkness that surrounds what people actually pay for their drugs. If you are like me, you have absolutely no confidence that either the full or discounted prices printed on our receipts from the drugstore have any basis in reality. We are led to believe that our insurer has obtained big discounts for us and that we should be grateful we do not have to pay even more than we do. Of course, without knowledge of what the drug maker charges its distributers, how much the pharmacy benefit managers collect and pay, the acquisition cost of the drugs to the pharmacy, the amounts of any rebates or other incentives, or even how much the insurer really shells out; it is impossible to know if anybody is making an effort to protect our interests as patients. Too many entities are feeding at the same trough.

National Average Retail Prices.

Back in 2012, CMS, the agency that administers Medicare and Medicaid, began a program to determine just how much money was crossing the retail counter of chain and independent pharmacies. Information was collected directly from the pharmacies including payer, quantity dispensed, and price. This latter included the combined prices paid for drug ingredient costs, customer pay amounts, and dispensing fees. Alas, Congress killed the program before we the people could benefit from the results, but not before data for at least part of 2013 was collected and posted as a “draft” on the CMS website along with information about methodology. [Is there any doubt about whose interests were being protected by Congress? No doubt this represented another triumph of lobbying by industry.]

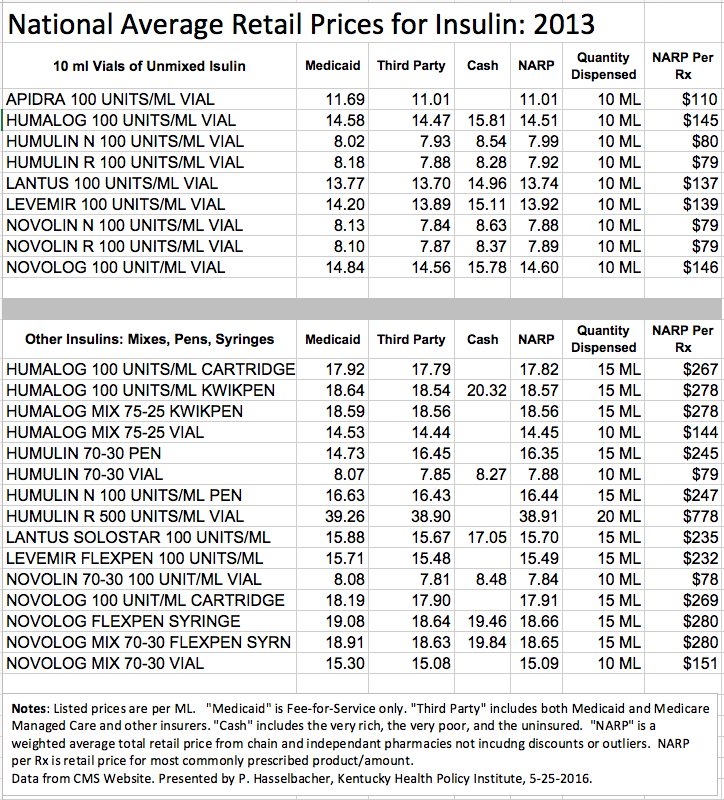

Below is a table of NARP for insulin products in 2013. From the complete list I abstracted all vials containing the industry standard of 10 milliliters (ML) of insulin at a concentration of 100 units per ML. Prices are given per ML for Fee-for-Service Medicaid, Third Party payers including Medicaid and Medicare managed care and other insurers, and Cash payers that would include the indigent and uninsured. A national weighted average of these is designated as the NARP [per ML]. The cost of the most commonly dispensed 10 ML vial can be calculated.

Results.

The older brands of human insulin (Humulin and Novolin) cost $79-80 per vial in 2013. The average prices of the five insulin analog brands was $135 which was 71% higher than the older human insulins. Are the newer insulins worth the money? What do they do that the old standards cannot? I do not know the answers but I am confident that we could all share in some savings. Here is an external link to the graphic visualization of the NARP data appearing below.

How much for convenience?

Pre-mixes of short and long acting insulin were uniformly more expensive than multi-dose vials of a single type. For at least some patients, the mixtures would simplify drawing up their doses or perhaps even eliminating the need for one or more additional injections. On the other hand, the fixed proportions of short and long acting insulin might not always be the best for a given person or situation.

It is obvious that insulin prepared in self-injecting “pens” or replacement 15 ml cartridges is more expensive than multi-dose vials. Refill cartridges by themselves were some 22% more expensive per ML than multi-dose vials. I do not know how to adjust for the cost of the injector or syringes in these comparisons, but there is a substantial cost for the convenience of not having to use single-use insulin syringes. There is no question though, that for some individuals with impaired vision, judgement, or manual dexterity, that the self-injecting pens or pre-filled syringes can easily be justified. Should they be paid to anyone on demand out of pooled premium or tax dollars? I predict there would be many answers to that question! I do not offer one here but in a world of limited resources it is ethical to say no.

I do not have a good idea how long a single 10 ML vial containing 1000 units would last for a typical diabetic. Hypothetically, if a 160 lb. person required 40 units of insulin per day, a 10 ml vial of a single type would last for 25 days requiring some 15 vials per year. For Novolin this would in 2013 have cost $1,185 and for Lantus, $2,055. [I welcome a more knowledgeable calculation!]

Other thoughts about the data.

I was quite surprised that there was not much difference in retail prices between Fee-for-Service Medicaid, managed care, or even cash! Cash payers paid more as would be predicted– but not as much as I expected. Medicaid is supposed to get “best prices” with substantial rebates on covered drugs used in its programs. I have to believe the amount of any rebate is not reflected in these retail prices. Such are the enduring mysteries of drug pricing that I must leave it at that.

National Average Drug Acquisition Cost.

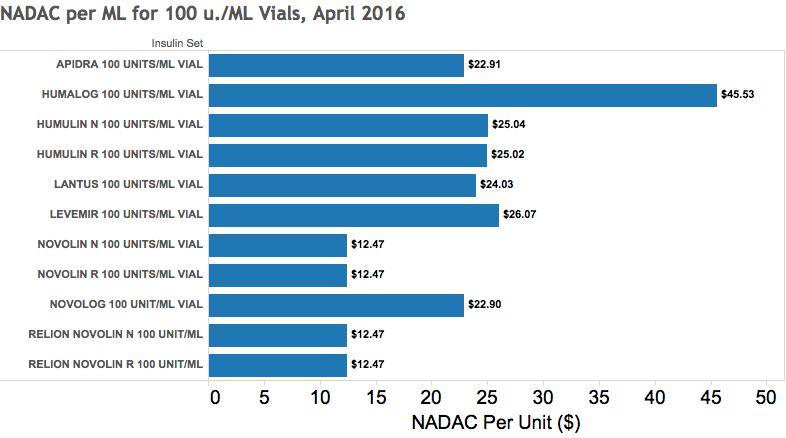

Unlike the Average Retail Price initiative which was begun at about the same time, this CMS program has endured. As I understand it replaces the unreliable “Average Wholesale Price” system that was subject to abuse. The purpose of the NADAC is to provide state Medicaid programs with the ingredient cost to a pharmacy so as to inform state negotiations with pharmacies, benefit managers, and other dispensers of drugs. These costs are derived from a sample of chain and independent pharmacies and refreshed at monthly intervals if not more frequently. The NADAC describes the cost of the active ingredient in a given drug and does not include dispensing fees or costs of transport or storage. A fair amount of detail is provided in the database including comparisons with prices of generic or similar drugs when relevant. Of course, in the case of insulin, no generics are available for comparison. Below are selected NADAC data for insulins as of April 2016. As was the case for Average Retail Prices, the NADAC prices are much lower than I was able to calculate from Medicare and Medicaid utilization data and I do not yet know what to make of the differences. An external interactive data visualization is available here.

Comparison with National Average Retail Price of 2013.

If the data is valid and I have interpreted the two datasets correctly, it is apparent that the prices of all the insulin products has risen, and in some cases, substantially. Recall that retail prices in 2016 will be considerably higher than specified by their drug acquisition cost that does not include non-ingredient costs to the pharmacy nor a profit margin. Nonetheless, even with these incomplete apples to oranges comparisons, the rises in costs in just 3 years are impressive. Humalog 100 numbers changed the most from $14.51 per ml. to $45.53. Lantus 100 went from $13.74 per ml to $24.03 but this reflects a price drop last year. The remaining insulin analogs were also in the range of $23 to $26 per ml. Humulin 100, a formerly modestly priced human insulin, more than tripled from $7.99 to $25.0 to join its upscale analog cousins. The human insulin Novolin 100 (and its Walgreen-branded version, Relion Novolin 100) remains the least expensive insulin available in the US with an average retail cost in 2013 of $7.88 rising to an average acquisition cost in 2016 of $12.47 for both rapid and slow acting versions and even for its short/long acting mix!

My hat is off to Novo Nordisk, Inc., the Danish multinational company that makes the Novolin family of human insulins, for keeping these prices lower. I leave it to Novo Nordisk to justify why its Novolog brand of insulin analog is so much more expensive. I leave it to my colleagues in general medical practice and endocrinology to explain why the least expensive Novolin is not appropriate and used more for all diabetics! Having offered this challenge, I grant that there will be good reasons to have the larger armamentarium available but I doubt that exceptions to the rule of “use the least expensive effective drug first” will justify the insulin prescribing profiles in Medicare and Medicaid that initiated this series of articles. Surely we can more efficiently distribute resources in the interests of our diabetic patients and neighbors. None of this is possible however without more transparency in what our drugs cost. We maneuver today in deliberate confusion that cannot be justified.

As always and especially in the realm of drug prices, it is possible I have misinterpreted some of the data or made other errors. Help me correct these. What can be learned from consideration of how insulin is prescribed will apply to other drugs and many other medical services. What other families of drugs should I look at?

Peter Hasselbacher, MD

President, KHPI

Emeritus Professor of Medicine, UofL

25 May 2016