Some weeks ago, when public health experts were still visible in Washington, a reasonable-sounding set of guidelines for opening up the national economy was offered. Sadly, the White House seems now to place all responsibility on the individual states with minimal if any major Federal help. It is walking away from, if not contradicting, the advice of the best public health scientists the nation has to offer. I fear that things are going to get interesting quickly and that we will land in an uncharted place somewhere between good and disastrous.

With individual states beginning to open up their economies in different ways and to different degrees, it is apparent that our ability to identify new cases of Covid-19 infection early, to do so in unexpected places, and to be willing and able to do something about it will be critical.

What is a “Mini-Update?”

The Wall Street Journal and other publications often offer a “Coronavirus Daily Update” sidebar with a simple list of Total Cases, Total Deaths, and Recoveries for both the United States and globally. When applied to a given geographic area, these three totals are important elements for predictive epidemiologic models. The fact that the numerous models offered today differ widely (or even turn out to be wildly wrong) confirms the truism that any model is no better than the assumptions it makes and the data available to it. By themselves, these high-altitude aggregate numbers are not fine-grained enough to help us predict the future for Kentucky. I do suggest there are some insights to be gained by examining them. In any event, the numbers are sobering.

What might we learn?

Readers of these articles may notice that I have been educating myself (and I hope some of you) about how we can best use the limited and imperfect epidemiologic data available to us to monitor the opening our economy. Are we are on the right path– or are we falling off the wagon? This is today the major healthcare challenge facing us as a nation. What might we learn from countries where the epidemic started earlier? How are we similar or dissimilar?

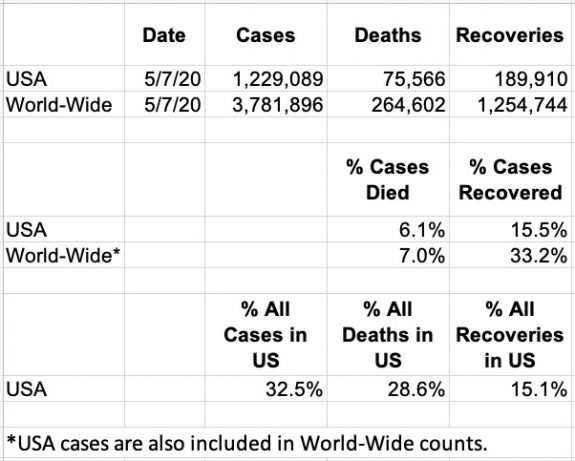

The typical mini-update extracted below was taken from the May 7 print edition of the Wall Street Journal. [Yes I read the Journal daily… and the New York Times, and the Courier- Journal!] We are given world-wide numbers of Cases, Deaths, and Recoveries and the same numbers from the United States. Aside from the impact of seven-figure aggregate cases, what other insights might be extracted? Here are a few that occur to me which I think are relevant to tracking our epidemic in Kentucky.

Caveats:

It goes without saying that individual countries (and Kentucky counties) have widely differing health care systems, public or otherwise. The social infrastructures that allow collection of reliable data range from excellent to non-existent. (We are somewhere in between.) We must assume that many cases and deaths go unrecognized or under-reported in a timely way– if at all. Transparency or even honesty are sometimes in question.

The global data in this specific summary version includes that from the US. By lumping the United States’ statistics in with the global pool, any potential differences (and there are some whoppers) will be averaged out. Our global peoples live different lives with different burdens of medical and nonmedical determinants of health status and outcomes.

That said, here is what stands out to me.

- Although the United States came late to the game having imported our cases from China and Europe, a whopping 32.5% of current worldwide Corona virus cases were home-grown in the United States. We provided a fertile soil.

- Of deaths so far, 28.6% have occurred in the United States. Recall however, that the American part of the pandemic revved up later, and that there are built-in lag periods between getting infected, getting sick, and dying– if that is the eventual outcome.

- As of the date of the report, of the listed cases in the United States, 6.1% have died compared to the worldwide observed mortality rate of 7.0%. This small difference is unlikely to be meaningful given issues such as disease timing and variation in data collection.

- Note also that the computed death rates are only observed interim death rates. We hopefully assume that the eventual overall mortality rate will be lower, but we will not know a final overall case mortality rate with confidence for some time. Given our presumption that we have an excellent healthcare system, should we I have be surprised that our own observed US mortality is so close to that of the rest of the world?

Mortality rates are based on the number of known cases. How does one know this? Testing-data is not included in this Mini-Update. Covid-19 virus testing in the US has been a weakness. If we have been testing mostly sick people, our observed mortality rate would be higher than if not. Some countries have done better in testing their populations. A basic tenant of clinical research is that when comparing different populations, data must be collected using the same standardized methods. I do not think we can yet say our mortality rates will be either better or worse than other advanced countries. Yes, it might be worse.

- About Recoveries. The number of cases that have recovered is important for models of epidemiologic prediction. Individuals who have had a given disease and survived must be removed from the population still subject to infection or death in order to accurately predict the course of an epidemic. Hopefully, all or most of the recovered will be immune for a while and not be susceptible to recurrence. (We do not know this for sure yet.)

According to this edition of the updates, the United States has only 15.1% of known global recoveries despite having 32.5% of all cases. World-wide, the percent of all cases that are reported to have recovered is 33.2%. Knowing what happens to a Covid-19 patient when they leave the hospital or their medical-care provider requires an enormous amount of medical detective follow-up. For countries with an integrated healthcare system and a well-functioning and integrated public health system, tracking individual cases is at least conceptually possible. Alas, neither is the case in the United States. Our healthcare system is siloed, and our public health system is fragmented and has been starved of both priority and resources. My working hypothesis is that we will be handicapped in tracking former cases for some time.

The data underlying this Mini-update and many more comprehensive updates is available from several well-curated data bases available to all. Some of these are easily downloadable for independent analysis. Many will be doing the latter as I hope to as well. I will start by comparing Kentucky’s numbers to the states immediately surrounding us and to those who have taken other paths, some bolder, to opening up their local economies. With some transparency and trust, we can learn from each other– as countries, states, and communities!

Some Take-aways for Kentucky.

• We need to do better with testing in order to identify the rising epidemic hotspots that are certain to arise. It is not just the sick and caregiver that needs to be tested.

• Local public health agencies need to be working from the same script if their numbers are to be added to the denominator and compared across the state. Accurate and timely reporting to a central public health entity is critical.

• Case finding and tracing both forwards and backwards is essential. We are not even close to what we will need right now.

• Providing comprehensive and essential medical care to people includes knowing what happens to them after they go home. For the most part we are poorly equipped to do this. We are only beginning to know what Covid-19 does to us medically long-term. Our current healthcare system has failed us. In my opinion we need to think seriously about a major do-over. More about that from me and others sure to follow.

• Just as reporting global numbers can provide only an overview, reporting state-wide Kentucky numbers will only average-out what is happening. We must monitor and respond to Covid-19 at the micro-locality level.

• The state as a whole is vulnerable to the standards and practices of every other geographic and governmental entity within it. As a state, we are held hostage to each other. Making unjustified exceptions increases that vulnerability. By all means it is necessary to test the waters and return to some new normal. The journey should be guided by the best public health and medical science available, and not forced by armed protestors, or to win an election, or to escalate the social-issue battles that have torn us asunder as an increasingly ineffective society.

Peter Hasselbacher, MD

Emeritus Professor of Medicine, UofL

President, KHPI

11 April 2020