Why is your heart the punching bag?

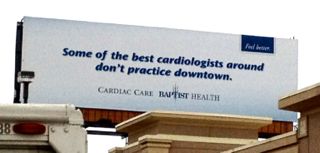

On the way to my gym on Shelbyville Rd., I noticed a billboard advertising Baptist Health’s cardiology service. It advises me that “some of the best cardiologists around don’t practice downtown.” This, of course, is true. The ad is an obvious riposte to some of the advertisements of downtown hospitals, one of which advised that for your best chance of surviving a heart attack, you should take the next exit. If corporations are people, it is now getting personal!

It’s hard not to notice that our area hospitals advertise their cardiac services heavily. Each one is said be the better for you, and amazingly, many can produce reports from external review organizations appearing to back up their assertions. What is distinctly lacking, in my opinion, is objective evidence in the promotional material to support claims of excellence. For most of the Fall and Spring of 2008-09, I drove several times a week past the sign (and the exit) on Interstate 65 that promised my best chance of surviving a heart attack. I wondered on what basis the hospital could make such a claim. When I learned that Medicare’s Hospital Compare was then calculating risk-adjusted mortality following heart attack, I had to check it out. In fact, not only did the advertising hospital not have the best survival rate in the city, it had the lowest. Nevertheless, the sign stayed up for many months. Today the mortality rates have evened out, but is all such advertising so much puffery? How are we to know?

Why are cardiology patients fought over?

It is not a state secret why cardiology, cancer, orthopedics, or neurosurgery are advertised so heavily by hospitals. These are among hospitals’ most profitable services. My former hospital lobbyist colleagues were quite open in admitting that cardiology services are overpaid by Medicare and other insurance companies. According to the bank robber Willie Sutton’s law of medicine, that’s where the money is. I will say more about this in another post because an absence of profitable services is relevant to the financial difficulties of Louisville’s University Hospital. In my opinion, the other downtown hospitals have helped to keep University Hospital in its place.

The Baptist billboard is clever, and reminds me of the series of billboard ads for hotdogs and whiskey also containing witty one-liners that we all chuckle at. I would not be surprised if the same advertising agency was responsible for some of the medical ads as well. That is, a very depressing thought however. At a time when food and dietary supplements are marketed as though they were medicines, medicine is marketed as though it was soap powder. Are we really that gullible or so easy to manipulate? I have already told you how I feel about the quality and ethics of some of these advertising campaigns. If you believe everything you see and hear, you will be badly served. Continue reading “The Cardiac Gloves Come Off!”