Last Fall I got way behind on my writing and have still not caught up. The proximate reason was a road trip, or rather a riverboat cruise behind the former Iron Curtain down the Elbe River from Prague to Berlin. On the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of World War I, and the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, the trip was informational as well as enjoyable. Although I (and my spouse) was looking forward to a holiday from my writing, it proved impossible to avoid thinking about health policy. Allow me to share two examples of how I was hit over the head by medical advertising.

America abroad.

Imagine my surprise as I rounded a corner in the small riverside town of Litomerice— whose name I could not pronounce, let alone spell— to be confronted by the sign below. I was stunned to the point that during the subsequent arranged tasting of truly excellent Czech beer, rather than enjoying the moment, I pressed our English-speaking host for information about the sign.

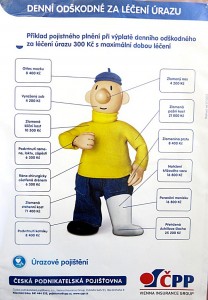

The sign sat outside a bank that was also in the business of selling, or at least arranging for, some sort of supplemental health insurance. I asked a new friend why the phrase “Best Doctors” was in English instead of Czech. He thought that perhaps it sounded more exotic. I asked about the criteria used to identify the “best” doctors. The answer was a more or less skeptical– “because they say so.” With all I have been writing recently about efforts to judge the quality and safety of healthcare, you can imagine that I became obsessed with learning more. While my long-suffering wife went on to admire the wonderful old architecture, I almost missed the boat by by ducking into into an insurance office where I found marketing materials stunningly similar to those we see in America. Little arrows on an illustration pointed to various body parts highlighting the expense should some problem occur at that location and giving the impression that Czech citizens would be on the hook for medical expenses should they get sick. I had assumed that in this formerly communist country there would be some sort of national health insurance and wondered what the driving force behind the marketing of private health insurance might be.

I had assumed that in this formerly communist country there would be some sort of national health insurance and wondered what the driving force behind the marketing of private health insurance might be.

Czechocare.

As it happens, the former Soviet-styled healthcare system was inadequate to deal with the changing medical needs of the Czechs and was replaced, beginning in the 1990s, by a “compulsory health insurance model” that today has much in common with with Obamacare, albeit with price-controls for drugs. There are user fees, out-of-pocket limits, and provider networks in which your doctor may or not be a participant. The government is still the major purchaser of services (as it is in America) but it is easy to understand why other insurers are competing with each other for their piece of the action. As in America, marketing techniques attempt to distinguish health plans based on claims of better doctors or better healthcare. I refer you to an excellent article here.

American exceptionalism.

Unlike in America, there seems to be a fundamental proposition that “we are all in this together— that no one is left at the side of the road.” There are also assumptions of responsibility on the part the citizenry. Immunizations are compulsory, as are preventative examinations. (I do not have information about whether there is a presumption of voluntary organ donation, or even if transplantation is available.)

Best doctors as commodity.

When I got back home, I scratched around the internet a little. I found the stock image used in the Czech ad available for purchase from Getty Images. Apparently there is an emerging business model in America and Europe that provides support to private insurance companies by offering doctor-rating services or assistance in identifying consultant specialists. As far as I can tell or translate, the evaluation is performed using proprietary or otherwise undefined methods. My readers will surmise that I have problems with even well-described attempts to simplify and objectivize the quality and safety of healthcare! The European insurance plans or doctor-finding services illustrated above may be excellent, but I have no way of knowing what the Czechs are getting for their healthcare dollar any more than the average American on the street does at home.

Why I can’t stand watching American television any more.

Even before I got home, I got clobbered with American marketing of healthcare. Killing time in the air, I read through United Airlines “Hemisphere” magazine of November 2014. Fully 17% of its 164 pages consisted of ads by healthcare organizations or providers. If the 26 pages of airplane business and maps at the end are not counted, one in every 5 pages were healthcare ads. Five of these ads made specific claims of being a best hospital (some with U.S. News and World Reports badges to prove it) or of having the best doctors.

I arrived home to find newly-erected billboards and banners by local providers claiming to be the “best” for specific services. I really wish they wouldn’t do that, or at least if they did, to present all the numbers underlying their commendations, not just the best ones. Fully-informed clinical consent requires presenting the good, the bad, and the ugly. Why should not the same principles apply to advertising for medical services?

In my vision of healthcare for the new millennia, I bewail the selling of vitamins, food supplements, and snake-oils as though they were medicine; and the marketing of healthcare as if were soap powder. At least in our global economy, for better or for worse, we not alone in how we sell things. Until we are able to recognize that there is a difference, and that we are as a society are no healthier than the sickest among us, we will never have true healthcare reform, or for that matter effective healthcare worth having.

Peter Hasselbacher, MD

President, KHPI.

Emeritus Professor of Medicine, UofL

January 8, 2015.